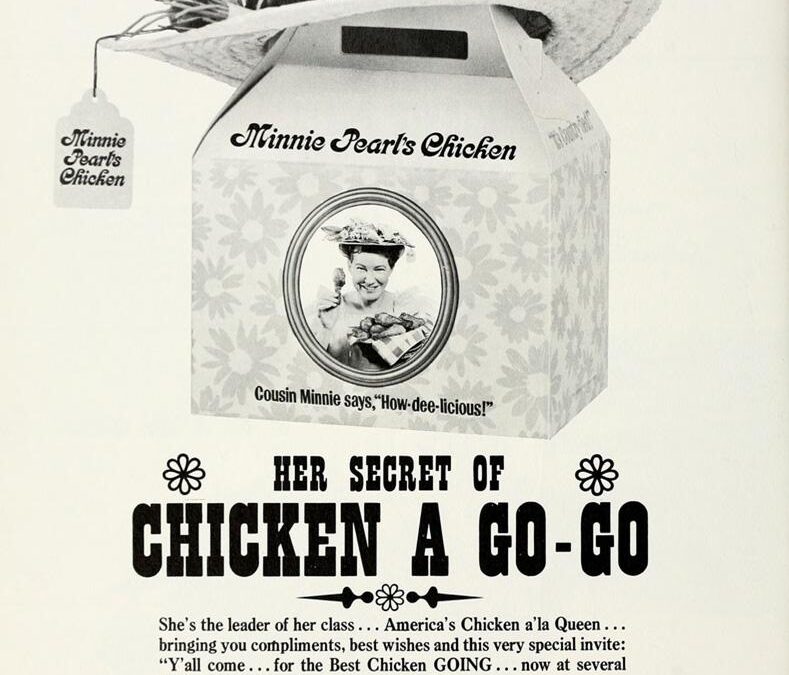

It seems reasonable that Minnie Pearl’s persona should be able to sell fried chicken, right?

After all the Centerville, Tennessee, native Sarah “Minnie Pearl” Cannon was, for her time, a country comedy phenomenon. With her frilly country dresses and straw hats adorned with colorful flowers and a $1.98 price tag hanging from its rim, Cannon spent 50 years on the Grand Ole Opry beginning in 1940. In 1969 she carried her humor to television as a regular on “Hee Haw,” where yet another generation of fans would come to know and love her.

So, when former Democratic gubernatorial nominee John Jay Hooker Jr., a charismatic and somewhat eccentric Nashville attorney, conceived of a fast food chain called Minnie Pearl’s Fried Chicken, it seemed like a natural fit.

To Hooker it must have appeared that Kentucky Fried Chicken was an overnight success. In reality “Colonel” Harlan Sanders had begun selling his specialty fried chicken out of the back of his gas station in the 1930s and began franchising it in 1952 with 600 locations by 1964. When Nashville businessman, Jack Massey, and Louisville lawyer, John Y. Brown, purchased the Kentucky Fried Chicken empire from Sanders for a mere $2 million dollars, it saw immediate and very lucrative growth that launched it into the international, multibillion dollar company it has become.

Hooker and his law partner and brother, Henry Hooker, convinced Cannon, an educated, intelligent woman despite her simpleton comedic character, that if Colonel Sanders could sell fried chicken, they could sell more.

The Hookers admitted they knew nothing about cooking and had never run a restaurant, yet they were so optimistic about the future of Minnie Pearl’s Fried Chicken that they projected the franchise would have 500 stores by 1970. Politicians, activists and investors purchased stock at $.50 to $1 a share in faith that the Hooker brothers knew what they were doing. Soon there were 300 franchises, and the stock value soared. Investors became millionaires.

“It’s going to be fun for me,” Cannon reportedly said, but that was going to prove very untrue.

The Hookers took the company public in 1968, but the accounting method they used with regard to franchise fees and stock value, though allegedly an accepted practice at the time, drew the attention three years later of the Securities Exchange Commission, which launched an investigation to determine if the company had engaged in any criminal wrongdoing.

“If the food does not agree with the people who are supposed to patronize all these outlets, then Minnie Pearl’s will find itself with a balance sheet full of deserted buildings,” Fortune Magazine stated in a prophetic October 1968 review.

To make matters worse, in early 1969 there were only 40 restaurants open, 100 under construction and 300 under development. Customers did not like the taste of the chicken nor the fact that taste and quality was inconsistent.

The Hookers changed the company name to Performance Systems Inc. and by March 1969 had sold hundreds of new franchises in an attempt to grow the company and recoup some of the early losses. The menu was expanded to include pizza and roast beef. Nonetheless, PSI lost $5.5 million during the first half of 1969.

Finally, the SEC’s investigation found that the company had filed financial statements that were false, rewriting the company’s 1968 annual report to show that the company lost $1.2 million rather than earned $3.2 million. A class-action lawsuit was filed by PSI’s shareholders, but they only recovered a small portion of what they invested. By 1974, the stock was less than a quarter a share. It was all over by the end of the ‘70s.

Cannon was completely cleared of all wrongdoing, but she was embarrassed that the name of her beloved Minnie Pearl character was associated with one of the restaurant industry’s legendary fiascos.

This copyrighted story by Sasha Dunavant was originally published in Country Reunion Magazine and Country Reunion News.