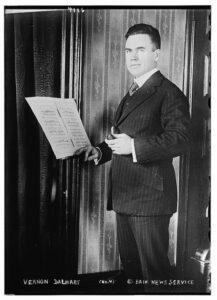

Country music’s first superstar was a Texan named Marion Try Slaughter, who was known professionally as Vernon Dalhart. The prolific and talented singer had sold millions of records three years before Jimmie Rodgers, often heralded as Country’s first star, was even recording.

Dalhart took his stage name from two Texas towns where he had worked as a cattle punch in the 1890s. He began singing as a toddler, with initial performances at the Kahn Saloon in Jefferson, Texas, when he was a teenager. It was at the back entrance to this same saloon that his father was shot and killed by his mother’s brother in 1893, presumably because of the elder Slaughter’s domestic abuse. In 1981 the Texas Historical Commission placed a marker at the building commemorating Dalhart’s contributions to the early commercial success of country music.

By the 1900 U.S. Census, Dalhart can be found in Dallas, age 18 and single, working in a hardware store as a clerk and residing in the home of his widowed mother, Mary Jane Castleberry Slaughter. It was in Dallas he trained professionally. In 1902 he married Sadie Lee Moore, and daughter Janice was born around 1903 with son Marion Try Slaughter Jr. born the following year. The family relocated to The Bronx in New York in 1910, and Dalhart found work as a shipping clerk as he expanded his musical career.

According to information Dalhart provided in September 1918 for his World War I draft registration card, Dalhart was born April 6, 1882. At the time of registration, just months before the war to which he was never called to serve ended, he stated that he was employed as a professional singer by Thomas A. Edison in Orange N.J. Though an opera and popular music singer, he had already recorded his first song, “Can’t You Hear me Callin’, Caroline?” for Edison Records in 1917.

A news item from the May 19, 1919, issue of The Mountain Eagle, in Jasper, Alabama, informed that Dalhart’s concert was sponsored by Dilworth Jewelry Company.

“Whatever he sings from the most difficult operatic arts to the simplest heart song, Mr. Dalhart gives it with a voice that is bright, musical and pure,” The Mountain Eagle observed.

In addition to his repertoire of traditional songs and African-American melodies, his traveling performances throughout the country included more than 50 grand and light opera tunes delivered in his rich tenor voice.

Dalhart’s stunning Country Music career was launched with his 1924 double-sided hit of “Wreck of the 97” and “The Prisoner’s Song,” the latter of which was recorded on 53 different labels in an era where there were no recording contracts.

“Now if I had wings like an angel, over these prison walls I would fly, and I’d fly to the arms of my poor darlin’, and there I’d be willing to die,” Dalhart sang, touching the hearts of listeners world wide and selling millons of copies.

In 1998 his recording of the song was honored with a Grammy Hall of Fame Award.

Dalhart biographer, professor and musical historian Darrell Haden wrote in 1970 that before the Country careers of the Carter family and Jimmie Rodgers even began, “Dalhart had been enjoying not only a 25,000,000~seller, retailing on records costing from a dime to over a dollar, but also a simultaneous hit to keep his name on the lips of record buyers internationally.” Haden was referring to Dalhart’s third hit, “The Death of Floyd Collins,” about a Kentucky explorer whose death in a Kentucky caving accident drew global media attention. He also made popular such songs as “The John T. Scopes Trial” about the Dayton, Tennessee, court case over the teaching of evolution, and “Little Marian Parker” about the kidnapping and murder of a California child, and other pieces inspired by news stories of his day.

It is estimated that Dalhart recorded more than 5,000 songs, with most of them being under the name Dalhart but many being released under one of the nearly 100 other recording names he adopted including hit favorite aliases, Al Carver and Mack Allen.

“These were the names which would enable Dalhart to play the field and avoid the encumbrances of exclusive contracts,” Haden explained. “Under these names he would freelance on all the major and on most of the minor recording labels in the eastern portion of this country and on many abroad as probably the busiest recording artist in the industry between 1924 and 1929.”

Dalhart became financially comfortable during those years. The 1925 New York State Census places the family on their estate in Westchester County, New York, where he is employed as a singer. They are still living there in the 1930 Census with him listed as a singer in the “phonograph” industry. It was not long after the crash of the economy in 1929, however, that the Dalharts lost their home and investments. Dalhart all but retired from the music industry during those economically devastating times, taking jobs like hotel clerk, night watchman and private voice teacher in nearby Connecticut towns during the 1930s to stay afloat. Dalhart worked in a Bridgeport, Connecticut, defense plant, shortly after the U. S. entry into World War II, and relocated his family there permanently in 1943. Both the Dalhart children settled in Bridgeport with Janice’s husband, Lewis Shea, and Marion Jr. each making careers in the banking industry. Marion Jr.’s career ended abruptly with his death in November 1944.

Dalhart became financially comfortable during those years. The 1925 New York State Census places the family on their estate in Westchester County, New York, where he is employed as a singer. They are still living there in the 1930 Census with him listed as a singer in the “phonograph” industry. It was not long after the crash of the economy in 1929, however, that the Dalharts lost their home and investments. Dalhart all but retired from the music industry during those economically devastating times, taking jobs like hotel clerk, night watchman and private voice teacher in nearby Connecticut towns during the 1930s to stay afloat. Dalhart worked in a Bridgeport, Connecticut, defense plant, shortly after the U. S. entry into World War II, and relocated his family there permanently in 1943. Both the Dalhart children settled in Bridgeport with Janice’s husband, Lewis Shea, and Marion Jr. each making careers in the banking industry. Marion Jr.’s career ended abruptly with his death in November 1944.

After suffering two heart attacks, Dalhart died Sep.15, 1948, with Sadie following in 1950.

Though he lived his last 20 years in virtual obscurity, Dalhart’s fans long sought recognition for him and for the Country music industry he helped to shape. He was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Association Hall of Fame in 1970, into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1981 and the Texas Country Music Hall of Fame in 1981.

“It was an even more natural matter for him to become the nation’s first great country music recording artist than it was for him to build distinguished careers, first in classical and then in popular music,” Haden said of Dalhart. “That such a phenomenon could occur in the American music industry may seem difficult to believe.”

This copyrighted story by Claudia Johnson was originally published between 2012-2023 in Country Reunion Magazine and Country Reunion News.